Since SPINELESS has been out in the world, I’ve discovered one very simple jellyfish thing I never did: draw a jellyfish. Sure, I doodled jellyfish in the edges of my notes and I sketched Picasso-esque outlines of jellyfish on nametags and business cards so people would remember that I was that person writing about jellyfish. But I never really drew a jellyfish. (When it came to my book, I farmed the drawing out to the incredible Rachel Ivanyi) who beautifully illustrated the section openers.)

Since SPINELESS has been out in the world, I’ve discovered one very simple jellyfish thing I never did: draw a jellyfish. Sure, I doodled jellyfish in the edges of my notes and I sketched Picasso-esque outlines of jellyfish on nametags and business cards so people would remember that I was that person writing about jellyfish. But I never really drew a jellyfish. (When it came to my book, I farmed the drawing out to the incredible Rachel Ivanyi) who beautifully illustrated the section openers.)

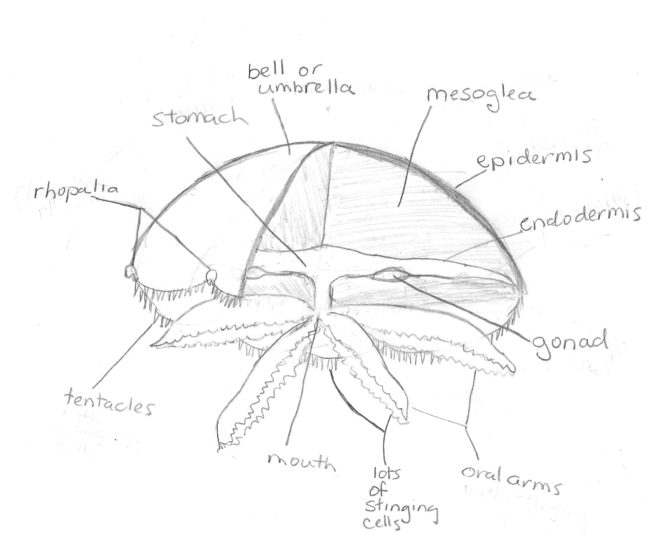

But recently, readers have contacted me suggesting that a labeled drawing of a jellyfish would be helpful. It’s not like jellies have any of the familiar parts we recognize on other creatures, things like arms and legs, or even faces. A visual to keep, say, tentacles straight from oral arms makes good sense.

So, I’ve attempted to draw my first admittedly-amateur jellyfish. There’s a reason I’m a writer and not an artist, and I hope that you can look past all the ugly eraser marks. Because my background as a textbook writer means I do enjoy a good bold-fonted word, I’ve added vocabulary below.

The big domed part is usually called the bell, or sometimes the umbrella. In little jellyfish, the shape can be anywhere from torpedo to saucer. But in larger jellyfish, like the moon jellyfish I attempted to draw, it has to be fairly flattened in order for the hydrodynamics of its swimming to work.

Jellyfish only have epidermis (outside skin layer) and endodermis (inside skin layer), but no mesoderm to hold its organs like we do. Instead, inside is the very spinelessness of the jellyfish, a gelatinous stuffing called mesoglea.

In the divots between the scalloped edges of the bell are very small organs called rhopalia, which have an outsized influence on jellyfish behavior. They are the animal’s sensory centers–like mini faces. Moon jellyfish have two eyespots on each of their rhopalia, but famously, box jellies have six different types of eyes on each of their four rhopalia for a total of 24 ways to see the world. The rhopalia also contain fields of cilia for sensing currents and chemicals, and a balance organ that works like the balance organs in our inner ears. Near each of the rhopalia is a pacemaker that takes in all that sensory information and controls how fast the jellyfish pulses. If it senses something unusual, the pacemaker speeds up, and the jellyfish quickly pumps away from danger.

The tentacles are the skinny tassles that hang off the underside of the bell. In some jellies they stretch for feet or yards, but in this moon jelly they are just a short fringe. The tentacles contain a lot of stinging cells for capturing prey.

The pieces that look like veils or draperies are extended lips called oral arms. They also contain a lot of stinging cells and lead to the mouth. The mouth is the only way in and out of the medusa’s body, so whatever goes in and can’t be used must come back out the same way. The mouth leads to a stomach, which branches off into digestive canals that take nutrition throughout the animal. Eggs or sperm–jellyfish are either males or females—form in the gonads that are situated alongside the stomach. When the animal spawns those eggs or sperm travel through the stomach and out the mouth.

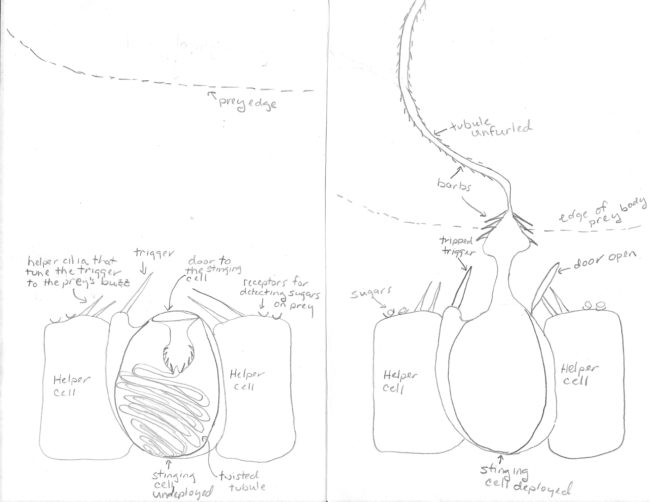

Those previously mentioned stinging cells, which are also called nematocysts or cnidae, are at the center of a jellyfish’s success story. They are highly sophisticated pieces of biological equipment that probably allowed jellyfish to remain fairly unchanged through more than half a billion rollicking years of evolution.

Those previously mentioned stinging cells, which are also called nematocysts or cnidae, are at the center of a jellyfish’s success story. They are highly sophisticated pieces of biological equipment that probably allowed jellyfish to remain fairly unchanged through more than half a billion rollicking years of evolution.

An un-deployed stinging cell is mostly taken up by a capsule with a twisted up hollow tubule inside. It’s guarded by a trigger made of a bundle of cilia. The trigger is pulled only when it detects both the smell and sound of prey. Then the cell swells with so much fluid that a door at its end flies open and the tubule unfurls with an acceleration five million times that of gravity impales the unfortunate plankton. It’s the fastest known motion in the animal kingdom. The tubule is often armed with spears and claws and poison is pumped out through holes in the end. I’ve tried my hand at a stinging cell drawings—both undeployed and deployed–for you too.

I’m feeling gracious, so no vocabulary pop quiz today! But I do think these diagrams will be helpful if you read SPINELESS. And I hope you do. Because the most important thing I learned in my years researching jellyfish is that despite their unfamiliarity these amazing creatures with all those remarkable anatomical tools aren’t as alien as they might seem. Indeed, they share our planet’s precious seas with us. And their success in those seas can signal an ecosystem imbalance from overfishing, coastal development, pollution, the transport of invasive species, or ocean warming. But, all the jellyfish can do is signal. We are the ones who must take responsibility for the ocean’s health, which, of course, is our health too.

Ah! I was wondering why there was no diagram in the book. This is really useful, although now I’ll have to go back and start from the beginning to follow all the descriptions/narrative of the anatomical parts!

Thanks Celia! I’m so glad you have been enjoying the world of jellyfish!