At the Society for Environmental Journalism's Annual Meeting in 2022, I was asked to moderate a session on ocean plastic, a topic I've followed for about a quarter century.

The issue came on my radar back in the 1990s, when my friend and fellow graduate student Tom Hayden went to Washington D.C. for a writing fellowship at USNews & World Report. One of his first stories was about Captain Charles Moore, who discovered and then made famous the collection of trash in the center of the north Pacific gyre, that's been called the garbage patch.

Around that time, I went on a research cruise about 500 miles off the coast of Iceland. I remember one afternoon, standing on the fantail, the back of the ship, and looking out to sea. Occasionally seabirds flew by, even that far away from land. That day I saw, a seafaring tern, it's legs wrapped in a six-pack ring. And I wondered if there was possibly a garbage patch in the Atlantic too. Now we know that there are plastic garbage patches in all of the gyres of the world's oceans.

A few years later, pondering the issue and trying to figure out what it might look like for me to be a writer, I wrote a kids book called Mermaid Tears, where an intrepid mermaid discovers that rather than crying bits of glass, as mermaids always had, she had begun to cry bits of plastic, called nurdles. Nurdles, the seed-shaped pre-production form of plastic, are now found on beaches all over the world. (I never did find a publisher for that story. But I still have it if anyone is interested!)

This year, over winter break, I stumbled onto a fascinating project about nurdles, called Nurdle Patrol. It is a citizen science endeavor out of Port Aransas that is for the first time, mapping the abundances of plastics along the Gulf Coast. Not surprisingly, nurdles are found in greatest abundance near the plastic manufacturers from Houston to Louisiana. But they are loose everywhere in the world. The lead on the project, Jace Tunnel, finds them along railroad tracks, in streams, and ponds. He produced an utterly engaging video of nurdle patrol from one end of the Gulf to the other, and rarely did he come up empty handed.

When I heard that Jace was willing to be on the plastics panel, I immediately said yes to moderating it. I wanted to find out more about his work. He said that more than 1.6 million nurdles had been collected over 6000 surveys, with efforts continuing to grow. The panel was rounded out with Luke Metzger of Environment Texas, who works on policy, pushing brands to limit their use of plastic. And Joshua Baca, from the American Chemistry Council.

Sometimes, at meetings like this, happy hours are actually just as important as the formal meetings. The evening before my panel at one such happy hour, I met Anja Brandon from the Ocean Conservancy. For her PhD research at Stanford, she worked on plastic recycling. She joined the Ocean Conservancy to bring the issue of ocean plastic to the front of its mission. For 35 years, the Ocean Conservancy has hosted an international plastic clean up, and now there was enough data to address plastic policy.

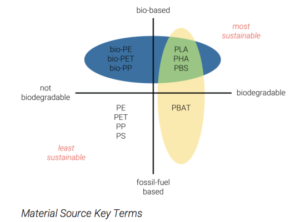

Anja has put together some of the most informative fact sheets on ocean plastic that I've seen. I want to highlight this graph, which includes two big ideas that I didn't understand before I spoke to her.

First, plastic can be made out of fossil fuels or out of crops like corn, but either way you end up with the same chemical compounds. So, while growing the feedstock from corn might pull some carbon dioxide from the atmosphere--a potential benefit for climate change--it makes no difference when it comes to ocean plastic. And if those corn crops are fertilized with fossil fuel-base fertilizers, that climate change benefit may be diminishing.

Second, there IS a kind of plastic that's compostible. I remember several years ago buying some "compostible" plastic forks. I thought watching them degrade would be a great science fair project. My son Ben and I buried them in the garden. And then we dug them up every month, and saw not a single change. Anja confirmed that the early form of "compostible" plastic actually wasn't. But there is a kind of plastic that is compostible called PHA, polyhydroxyalkanoate. And, it breaks down in the ocean too. But maybe because of that early gaff with "compostible," PHA is not widely used and currently only accounts for 2.8% of global biodegradable plastics.

A few weeks before the meeting, I was contacted by a colleague of the Assistant Secretary for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, Monica Medina, asking if she might make a brief announcement before the ocean plastics session. Ms. Medina had recently returned from Nairobi, where she'd negotiated the first international treaty to move away from plastic. When she spoke, Ms. Medina said that we can all agree that we don't want to live in a world full of plastic trash.

In my introduction to the panel, I said that we've learned a lot since the days of the garbage patch discovery. Most importantly, we've learned that plastic is really not an ocean issue, it's a land issue. Ocean plastic comes from us on land--a dump truck of plastic enters the ocean every minute--and it's up on land that we need to turn the spigot off on plastic. In her address, Ms. Medina said, this landmark treaty is the start of turning off the spigot.

But, there is still a lot of work to do to shut the valve.