The news is terrible. I find myself picking up my phone and clicking the “News” ap on my phone every hour, twice an hour, three times. I’ve read all the stuff about dopamine hits from clicking and I get it. It’s an addiction. Plus, like I said, the news is bad so the clicking and the ugly just feeds on itself. I’ve known I’ve needed to get out of the cycle for a while, and lo and behold, I think I found a way over Thanksgiving break.

The news is terrible. I find myself picking up my phone and clicking the “News” ap on my phone every hour, twice an hour, three times. I’ve read all the stuff about dopamine hits from clicking and I get it. It’s an addiction. Plus, like I said, the news is bad so the clicking and the ugly just feeds on itself. I’ve known I’ve needed to get out of the cycle for a while, and lo and behold, I think I found a way over Thanksgiving break.

I was visiting my parents, who live in St. Louis, and they have something we don’t have in Texas or when I lived in California either: a basement. And the great thing about basements is that things accumulate there in the way they just don’t seem to as much in attics. Maybe it’s because you don’t have to work against gravity to move things in.

It’s nearly impossible to go down in my parents’ basement without stumbling over something distracting. And this year, I found some old books from the 60s and 70s. They weren’t from my childhood. I’d never seen them before. It’s possible my mother, who was a teacher, collected them from the school library when they renovated. Or maybe my dad bought them in bulk at a used bookstore. There’s really no telling. But as I dug through the stack I saw that some of them were about science, and I grabbed a couple. They should be considered out of date, but what I found inside was new to me, and full of delightful writing and astonishing stories.

So, in the interest of spending time with information that feels somehow wholesome and healthy rather than click-bait-y and degraded, I’m going to start what I hope is a recurring type of post about these cool stories I’ve dredged up from the past, from actual pages rather than screens. I figure if they are news to me, they might be news to you too.

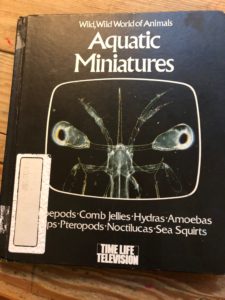

I have a feeling that this book, The Wild, Wild World of Animals: Aquatic Miniatures (what a title – not just Wild, but Wild, Wild!) by Time Life Television is going to be a treasure trove. I mean, it includes my beloved jellies first of all. And also, the writing is truly wonderful. I don’t know who the lead author Don Earnest is or was, but his writing is both poetic and rigorous, digging back into history and sharing cutting-edge research from the time. (Some of which, by the way, hasn’t been surpassed in the last 40 years.) Here’s a quote I love, “Observed under a microscope, a drop of seawater on a glass slide looks like the contents of a jewelry box spilled on a table.”

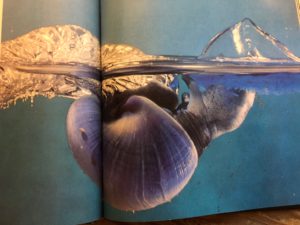

But the focus of this post isn’t microscopic. It’s a snail called Janthina (or sometimes Ianthina), because when I saw the picture above I thought, what the heck is happening there? I saw the snail floating upside down with an elephant trunk-like extension, a mass of something crystalline floating above the water, and the sail of the colonial jellyfish Velella, aka by-the-wind-sailor, which was also majorly involved in major oceanographic event called “The Blob” and the focus of another blog post a few years back. Also, some purple stuff under the Velella?

The caption explained that “Having immobilized Velella. . . Janthina proceeds to cut off chunks of its victim’s body. . .” Nothing like a bit of invertebrate predation to pique my interest.

Turns out Janthina is what’s known as a pelagic snail, meaning it swims in the open ocean rather than crawls on the sea floor. It uses the largest surface in the world–the air-water interface–as its home. It’s foot, the part that most snails crawl around on, has special glands that release a clear durable substance that it fills with air bubbles, becoming floating life-preserver. The snail’s shell is super lightweight too, to lighten the load and keep the whole creature buoyant at the sea surface. What’s more, the snail lays its millions of eggs underneath the bubble filled life preserver, so that it becomes a tiny crystalline nursery too. When the eggs hatch, the larvae just swim away.

But what’s happening on the right side of that photo with the Velella? The book explains that when Janthina bumps into another inhabitant of the air-water interface, Velella, it releases a “violet liquid.” Mmmm, violet liquid. The liquid sedates the siphonophore and the snail proceeds to casually snack away at its immobilized quarry. Creepy, almost spiderlike, right?

With that info in hand, I couldn’t help myself and stick to just the pages of the book and so I did a bit of Googling–careful to steer clear of the news websites.

In the book Pelagic Snails by Carol Lalli and Ronald Gilmer , I discovered Janthina are hermaphroditic. It’s a big ocean and there aren’t a whole lot of Janthina, so trying to find a mate isn’t easy. Janthina start off as a male, make some sperm packets that it holds on to its whole life, then switches to a female thats lay eggs. It’s worth pointing out that Janthina are nowhere close to being alone in this lifestyle. Loads of general solitary pelagic creatures, from arrow worms to comb jellies to other mollusks either switch sexes as they age or always contain both sperm and eggs and so can self-fertilize.

Physiology of Mollusca by Karl Wilber and C. M. Younge shared some fascinating information on the construction of the bubble float. If the snail gets caught underneath the sea surface, it’s not light enough to float. It has to swim and paddle with its little foot frantically upward. Once it manages to gets there, it kind of flattens its foot out on the water surface. Then it curves it like spoon, trapping a little bubble of air underneath, which is sealed up in its miracle-hardening mucous. (Are you making little spit bubbles with your tongue? Because I did.)

The bubble is attached to the growing float, where it becomes cemented in place. Once a snail’s got the system working it can manufacture a bubble a minute. There’s a note that when Janthina feeds on Velella, it usually jettisons its own float, because it gets in the way of eating and just hangs on to Velella’s float for support. (Which makes me wonder if the picture in Wild, Wild World of Animals: Aquatic Miniatures was a bit of a setup.)

But back to the purple paralyzing potion, what’s that about? Seems it’s still a mystery. While I do know that some mollusks are famous for making indigo pigments and others renowned for their venoms , I couldn’t find out anything about Janthina’s groovy “violet liquid.”

Let me know if you can. It’ll be a nice distraction from the news. I promise.

In a lifetime of beach combing and shell collecting, my most unexpected thrill was finding a Janthina shell washed up on a beach in Panama. I knew exactly what it was from one of the full color photographs in a shell field guide of mostly black & white illustrations. I was touched and amazed that this beautiful blue violet husk that had housed a creature floating on a raft of self-created bubbles far out at sea, now rested on the sand by my feet. It seemed such a rarity, like finding someone’s diamond ring in the high tide line.

Thanks so much for this beautiful post Ashley. What a gift from the sea!

I just came across this post out of the blue.

The janthina snail is truly fascinating, the ink even more so. Rabbi Isaac HaLevi Herzog, the first Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel believed this creature was the hillazon used in the production of tekhelet dye for ritual use in Judaism. Unfortunately little research was done on the snail to this day.

The ink is a very deep blue when it is first expelled from the janthina, although in pH environments greater than 5 it turns bright purple. The color of the ink can vary between blue and purple depending on the pH of the solution it is in, so perhaps the environment in the gland where the ink is stored is acidic?

The ink is heat tolerant and current tests reveal the ink to be light sensitive, at least when applied to wool. Perhaps it is a capable natural marine dye, although at this point no conclusions can be drawn.

I do not know if the ink has any an anesthetic properties. Recent unpublished chemical results indicate that there are multiple colored compounds in the ink, some blue and others purple. Hopefully a chemical structure of at least one of these compounds will be elucidated soon.