Plenty has been written and said about what's happening right now on the Florida Reef Tract, and so I've been slow to say any more, to add to the sadness. The Florida Reef Tract is the third largest in the world, about 380 miles long, stretching from north of Miami beyond Key West, to the Dry Tortugas. I've never been to that southern edge, but I've read the writings of the Alfred Goldsborough Mayer who set up the first tropical marine lab in the hemisphere there so that he and others could study the reef's abundant and vivacious coral, jellyfish, and other denizens. That was in 1905.

Plenty has been written and said about what's happening right now on the Florida Reef Tract, and so I've been slow to say any more, to add to the sadness. The Florida Reef Tract is the third largest in the world, about 380 miles long, stretching from north of Miami beyond Key West, to the Dry Tortugas. I've never been to that southern edge, but I've read the writings of the Alfred Goldsborough Mayer who set up the first tropical marine lab in the hemisphere there so that he and others could study the reef's abundant and vivacious coral, jellyfish, and other denizens. That was in 1905.

When I wrote Life on the Rocks, just three years ago, I fact-checked the sobering statistic that only 2% of the hard coral in the Florida Reef Tract still existed. It was hard for me to believe, but that was the official number. The rest had died due to disease and bleaching. Bleaching is the process in which the algal symbionts in the coral animal, the solar source of the animal's energy, are expelled. This breakup of what I call the "badass partnership" starves the coral. If the temperatures don't fall, the coral dies.

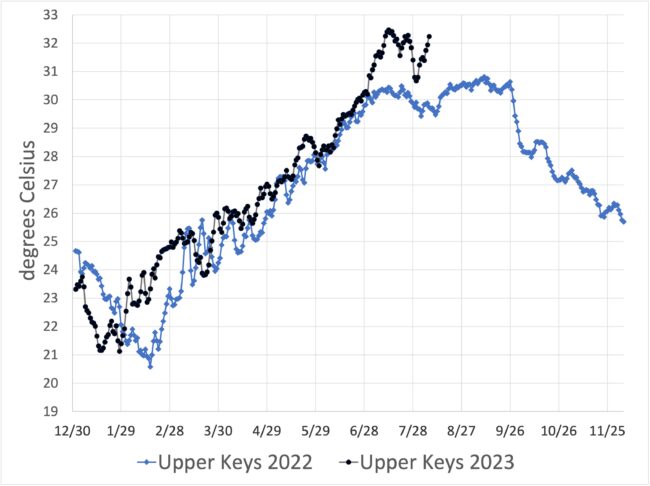

Over the last few weeks, the temperatures in Florida have risen to unprecedented highs. One oft-quoted and maybe record-setting number was 101 degrees Fahrenheit at a mooring in the upper Keys. While few coral live near that mooring, which is also in shallow water, I pulled down satellite data comparing last year to this year. The difference is a striking 2 degrees Celsius, which is close to 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

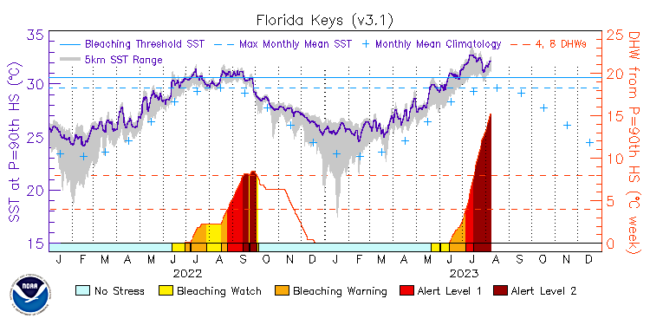

Coral scientists know it's not the absolute temperature that matters as much as the cumulative effect of time and temperature that seems to be the problem for the badass partnership. If temperatures increase by 1 degree Celsius for 4 weeks or 2 degrees Celsius for 2 weeks, it's a similar amount of stress, known as 4 degree heating weeks (DHW). Eight degree heating weeks is considered a threshold for bleaching.

As you can see in the orange-to-red peaks at the bottom of the graph to the right, which I downloaded from NOAA's Coral Reef Watch, the corals in Florida are experiencing close to twice the threshold, an infernal 16 degree heating weeks. (The right vertical axis is the one to look at.) And summer still has a long way to go.

My friend and colleague Tiff Duong, who lives in the Keys wrote me a month ago, "I went paddling the other day and the water was lake green and turbid from all the algae growth from the heat. It also smelled like death, and there were floating dead fish and sponges everywhere in the water. It was terrifying." Estimates are that 80 to 90% of the remaining coral will die. That will leave around 3 tenths of a percent of the hard coral on the reef.

Yesterday, I joined a webinar called "Coping with the 2023 Coral Bleaching Event" through the Coral Restoration Consortium. Some of the most excellent coral scientists and restoration experts from around the world were on the 2-hour call. They reported that this massive bleaching event started in May in the Eastern Pacific, where it affected Panama, Mexico, and El Salvador and now at least five countries in the Caribbean have confirmed mass bleaching.

There was much discussion of what to do. Photos and diagrams of ways to shade the coral were suggested. From Australia, the idea of using a fogging machine, like the kind used at rock concerts, is being tested. In Florida, coral scientists are actively pulling coral out of the water, loading them on a coral bus, and housing them in land-based aquaria. So far they have rescued 4,000 corals. The most repeated advice was to document the losses and take DNA samples of everything. We need to know what we are losing. We really need to know about the survivors.

The call continued later than scheduled, people clinging to the hope that maybe somehow something would make this crisis into something manageable. The real problem, we all know, is that up here on land, the decision-makers seem to be deaf to the screams from the sea. No one is taking climate change seriously enough.

Finally, an impassioned speech by Austin Bowden-Kerby, white-haired and bearded who spent a lot of time with restoration projects in the Caribbean, but now works in Fiji, found words to release the coral scientists back to triaging the reef. According to my scribbled notes, he said something like this: "We need to see every coral species as a highly endangered species, and we need to find long-term approaches to protect them. We need to keep hope in our hearts. I have hope in my heart because Mother Nature is working on it. She is always working on it. Our job is to keep the corals alive."